ELIZABETH STREB’S DANCE OF DESTRUCTION

NOTE: This essay appeared in the fourth and final issue of Biopsy (winter 2013). I have made light edits to smooth over some easily reversed blemishes while doing absolutely nothing to broaden the limits of the maturity under which the piece—influenced more by Maggie Nelson on cruelty than any appreciation for, or even sufficient knowledge of, the movement arts—was written. Incidentally it was the last piece in the issue, and an appropriate jumping-off point to all that followed.

***

Though conscience, emotion, and language are all cherished attributes among a whole swath of humanity, it’s really the body that gives them a sense of reality and purpose. Man, many believe, is nothing without his body. This is not solely due to the fact that the body encases what makes him conscious, but because he believes in its architecture, he believes that organic life is no more perfect in design than the human design. To nearly all humans, a well-toned body, whether from birth or from effort on his or her own part, is an affirmation, a prize even, for his or her own existence; whereas a largely imperfect body is cause for damnation. This is the popular sentiment and it is marketed as such, and as it has been with every other status quo sentiment, this too must be subject to hatred soon enough by the malcontents of the creative class.

And yet so revered is the perfect human form that it seems impervious to the jaundiced eye of artists Jenny Saville and Diane Arbus. Francis Bacon, to his credit, worked with well-toned bodies but managed, through intention or instinct, to degrade them into ugliness, so far as I can see. Perhaps, though, their mediums are insufficient. If one is to make the case that the toned body is every bit as breakable as the flabby body, it is only sensible that it be done in a form less passive and silent than painting or photography

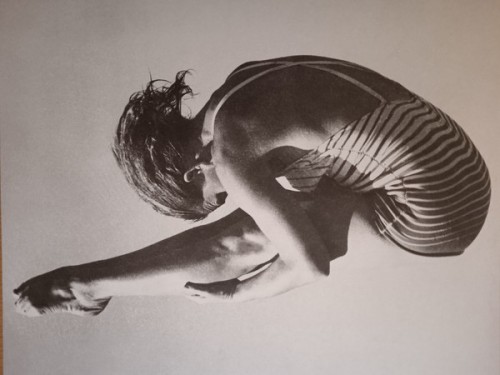

Elizabeth Streb thinks of herself less as a choreographer and more of an “action architect.” To her she is not merely an orchestrator of dances but a builder of movement, her primary building materials being the human form. As insufferable as that description sounds no one can deny its essential truth. Streb and her company of performers have lent themselves a staggering reputation for pulling off complex acts of movement, often given the audience the idea that some of her performers can walk on air. But then again so can the Cirque de Soleil, and so can the more traditional acrobatics.

What, then, truly draws people to Streb’s work? Her performers for the most part do not where costumes outside of uniform tights, the machinery she uses impresses in performance but would merely confuse if left dormant. All Streb really has to work with is the human body and the many ideas she has with which to take it to the absolute extreme of physical exertion, and perhaps beyond.

I am, I should note for safe measure, not privy to the workings of Ms. Streb’s mind. It is more than evident that she is a professional as well as artist who has a firm knowledge of dance, acrobatics and so on, which certainly informs her work. That being said, though, not all choreographers can boast her creative or coordinative abilities, in fact very few can. We are given the impression, through films like Black Swan, that all choreographers and directors are sadistic and perverse; they reconcile their sadism and perversion with arrangements of grace, romance, and tradition, but with a dash of “passion” on par with most trailer park dwellers. Streb counters these notions with an exposure of the sadism of staged dance.

The key to seeing how Streb uses the body is in the way a perfect body presents itself. Those with perfect bodies—that is, with fully developed muscles and minimal fat—are wont to flaunt their figures whenever possible. On the surface its language is one of affirmation. “I’m beautiful,” the body says, “this is my merit.” And this is what registers to those with the bodies and those who see the bodies. But as with every gratuitous exhibition there is an underlying negative language that, while not readily acknowledged by the fit bodied, beckons to those who can detect its call. “Destroy me,” it begs, “I can go no further than this form, I feel nothing at the sight of it, so tear me apart.” People have answered this call before of course, people like Ed Gein and especially Jeffrey Dahmer have ably dismantled the human form in impressive, if not exactly legal, ways. Similar Streb’s lack of restraint may be to Dahmer’s and Gein’s efforts, it is altogether distinct for its equal lack of crudeness and plethora of subtlety.

Like the bodies themselves, Streb’s work offers an interior and exterior message. The exterior message deals with notions such as man’s desire to defy and overcome gravity. The interior message, though, addresses and wages war on man’s delusion of physical perfection. She elaborates on this by using bizarre and complicated arrangements that stretch her dancers’ bodies to the utmost limit of their abilities making both physical harm and mental dysfunction not risks but conditions of the job. Dancers lie in a circle and duck a rotating steel bar; dancers leap and dodge swinging cinder blocks; dancers contort in boxed-in spaces; dancers run into invisible walls; dancers climb onto, into, and over massive gauntlet-like machines, one of which a dancer admits has a “guillotine” effect in the event of even a slight misstep. Every movement wears the performers down, as if they were being dismantled cell by cell, tissue by tissue. What ensues, if one looks past one’s own awe, is not so much avant-garde choreography but torture, a torture to which the performers willingly, whether out of masochism or out of not knowing any better. It is a torture that is both far more enhanced and far subtler than the type of transgressive performance art being undertaken in America’s military and clandestine prisons. And like the generic methods of torture, much of the creative center of Streb’s work is derived every bit as much from the conceiving of such tortures as it is from the carrying out of them.

When we step back and really look at Streb’s place in performance history, it seems better understood when compared to the British in-yer-face theatre of Sarah Kane rather than the ballet of Pyotr Tchaikovsky. There are no delicate princesses with dark sides waiting to be unleashed, but slabs of electrified meat which Streb takes hold of and prompts in whatever direction, stance, or position she chooses. The amount of control she exerts over the players should be considered as much a part of the show as the players themselves. It is a testament either to their absolute obedience or their open-mindedness (possibly both) that they allow this otherwise intrusive dynamic to take shape. The control is so overbearing that the only option of rebellion is bodily injury, which happened at least once in 2007 when a dancer fractured a vertebra during a performance of STREB VS GRAVITY. It’s a rather pyrrhic rebellion in any case. Even if control is wrested away from Streb it still gives her the desired result.

This is the ideal fate of a Streb dancer. But even if nothing along those lines occurs either in the long or short term, there is still the message her choreography sends to the audience. Some of them, to be sure, will still be purely stricken with awe by the spectacle like adolescent lovers, but others will take the hint. The era of the body-as-temple is over. Anybody as fit as those they saw on stage must be in constant vigorous activity to be of any use, activity that must put their very fitness at risk if they want to justify that fitness. In this new era the “hard bodies” of our society deserve only punishment, either self-inflicted or provided by someone else. Anything more is gratuitous; anything less is ugly.

Streb drives the point home all the more with her signature performance—strangely it is her simplest one as well. In Wild Blue Yonder (2003), seven dancers stand atop a platform high above the stage, and one by one they dive off onto a mat below. They are each in a stiffened, horizontal position resulting in a hard, facedown landing. Everything that makes Streb’s work so fascinating and perverse is rolled into this one number. She might as well be pushing them off herself, like throwing chum into a black ocean. Some in the audience are likely to be enchanted, while others might be perplexed or unsettled, but it is doubtless that a few remaining audience members will be disappointed that the platform wasn’t set higher.